How to Export Fresh Produce to Bangladesh Under a Letter of Credit (LC): A Step-by-Step Guide

Exporting agricultural products such as tomatoes, onions, and other fresh vegetables from India to Bangladesh is one of the busiest and most vital cross-border trade activities in South Asia. Every day, trucks cross land borders like Ghojadanga–Bhomra, carrying essential produce that directly supports food supply chains in Bangladesh and provides stable demand for Indian farmers and exporters. Because these goods are perishable and traded in bulk, ensuring secure and timely payment is critical.

This is where a Letter of Credit (LC) comes into play. An LC is a financial guarantee issued by a buyer’s bank that assures the exporter will receive payment once they provide the exact set of documents specified in the contract. For exporters, it reduces the risk of non-payment, while for importers, it ensures the seller only gets paid after shipping the agreed goods. In short, it builds trust and makes international trade possible, even between parties who may not have worked together before.

However, while an LC offers protection, it also comes with strict requirements. Even a small mistake — a missing LC number on an invoice, an incorrect date on a transport document, or a mismatch between the packing list and the proforma invoice — can lead to bank discrepancies. These errors may cause delays, extra charges, or even non-payment.

In this blog, we’ll break down the LC process step by step: from contract signing and document preparation to inspection, shipment, and final payment. Everything will be explained in clear, simple language so exporters can follow confidently.

What is a Letter of Credit (LC)?

A Letter of Credit (LC) is one of the most trusted instruments in international trade, especially in the movement of goods between neighboring countries like India and Bangladesh. It is essentially a financial guarantee issued by a buyer’s bank (importer’s bank) in favor of the seller (exporter). This guarantee assures the exporter that they will receive payment once they submit the documents specified in the LC, provided all terms are strictly followed.

There are different types of LCs, but two commonly used forms in perishable trade are:

- Irrevocable LC – Once issued, it cannot be cancelled or amended without the agreement of all parties involved (buyer, seller, and bank). This offers strong security to exporters.

- At Sight LC – Under this arrangement, the exporter receives payment immediately after the bank verifies that the submitted documents are correct and comply with the LC terms. This is especially valuable for perishable items like fresh produce, where timely payment ensures continuous working capital flow.

Most modern LCs are governed by UCP 600 (Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits), an internationally recognized rulebook published by the International Chamber of Commerce. This ensures that banks worldwide follow standardized practices when handling LCs, making cross-border transactions smooth and reliable.

In the India–Bangladesh border trade, where perishable goods such as tomatoes, onions, and vegetables are moved daily through land ports, the LC system reduces the risk of non-payment and builds trust between trading partners. It not only secures the exporter but also reassures the importer that payment will only be released once shipment and documentation are properly completed.

Trade Scenario: India–Bangladesh Border Export

The India–Bangladesh land border is one of the busiest agricultural trade corridors in South Asia. Every day, truckloads of fresh produce such as tomatoes, onions, green chilies, and other vegetables move across checkpoints like Ghojadanga (India) and Bhomra (Bangladesh). This trade not only meets the daily food demand in Bangladesh but also provides Indian farmers and exporters with a steady market for their perishable goods.

In a typical transaction, the exporter in India collects the produce at their warehouse, usually located close to the border. The goods are loaded onto trucks, and the transport route follows a direct crossing: from the Indian side at Ghojadanga to the Bangladeshi entry point at Bhomra. This short-distance land route is preferred for perishable items because it reduces transit time, preserves freshness, and lowers overall logistics costs compared to sea freight.

The payment method used for such exports is most often a Letter of Credit (LC) at sight, denominated in USD. This means that once the exporter presents all the required shipping and compliance documents to the negotiating bank, and the bank confirms they match the LC terms, the payment is released immediately. For exporters handling high-volume agricultural consignments, this quick access to funds is critical for maintaining cash flow and reinvesting in procurement.

In international trade, especially for bulk commodities like fresh produce, it is almost impossible to achieve exact weight and value during loading. To account for this, most Letters of Credit (LCs) include a tolerance margin of ±10% on both quantity and total value.

This means the exporter is allowed to ship up to 10% more or 10% less than the contracted quantity without breaching LC terms. For example, if the LC specifies 500 metric tons of tomatoes, the actual shipment can range between 450 MT and 550 MT. Similarly, if the contract value is USD 175,000, the final invoice may fall within USD 157,500 to USD 192,500.

This flexibility is especially important in agricultural exports, where factors like natural shrinkage, moisture loss, or truck loading variations can cause slight differences. The tolerance margin ensures such minor variations do not result in payment delays or document discrepancies.

Timeline of an LC Transaction

The process of completing a shipment under a Letter of Credit (LC) can be divided into four major stages: Before Shipment, During Shipment, After Shipment, and Payment. Each stage has specific responsibilities, and strict compliance is necessary to avoid costly discrepancies. Let’s walk through each step in detail.

1. Before Shipment

The before shipment stage is the foundation of any successful export under a Letter of Credit (LC). Mistakes at this stage often lead to complications later, including bank discrepancies, shipment delays, or even rejection of payment claims. For exporters dealing with agricultural products like tomatoes, onions, or other fresh vegetables, careful planning is even more important because the goods are perishable and delays can directly reduce quality and profitability. Let’s explore each component of this preparation phase in detail.

Contract Finalization

The first step is to ensure that the sales contract between the exporter and importer is comprehensive and aligns perfectly with the LC. This contract should clearly specify:

- Product details (e.g., fresh tomatoes, onions, vegetables) with HS code and ITC code.

- Quantity to be supplied, with possible tolerance (often ±10%) to cover natural variations.

- Price per unit and total value, usually in USD for cross-border trade.

- Incoterms such as CPT (Carriage Paid To), CIF (Cost, Insurance, Freight), or FOB (Free on Board), which define who bears transport and insurance costs.

- Shipment deadlines and the final delivery point.

- Payment method – clearly mentioned as LC at sight.

At this stage, exporters should request the buyer to ensure that the draft LC wording matches the sales contract exactly. Any differences, even small ones, may cause problems when preparing documents later. For example, if the LC specifies “export standard packaging” but the sales contract only mentions “carton packing,” the bank may treat this as a discrepancy. Aligning the terms early avoids such risks.

Inspection Arrangements

Most LCs, especially for perishable items, require an independent third-party inspection certificate. This assures the buyer that the goods are of the agreed quality and quantity. Commonly recognized inspection agencies include SGS, Intertek, Bureau Veritas, and Cotecna.

Exporters must:

- Book the inspection well in advance to avoid last-minute bottlenecks.

- Provide inspectors with access to the goods at the warehouse before loading.

- Ensure that the certificate language matches the LC wording exactly (e.g., “quality and quantity certified as per proforma invoice”).

Failing to obtain the inspection certificate in time may result in delayed shipment or non-payment. Therefore, exporters should make inspection part of their early planning.

Certificates

Two government-issued certificates are often mandatory in agricultural exports:

- Certificate of Origin (COO): Confirms that the goods were grown or produced in India. It is issued by authorized Chambers of Commerce or Export Promotion Councils. Exporters apply through recognized trade portals and must attach supporting documents like invoices and packing lists.

- Phytosanitary Certificate (PSC): Confirms that the produce is free from pests and diseases, meeting the importing country’s plant health standards. Issued by the Plant Quarantine Authority of India, it requires physical inspection of the consignment before shipment.

Both certificates are essential not only for compliance with LC terms but also for customs clearance at the Bangladesh border.

Transport Planning

Finally, exporters must plan the transport logistics. Since the LC requires a road transport document (truck waybill or consignment note), choosing the right carrier is crucial. The carrier must be able to issue a document containing:

- Dispatch date.

- Vehicle/truck number.

- Consignee details (as per LC).

- Freight terms (e.g., Freight Prepaid).

- Goods description and LC number.

A reliable carrier ensures the waybill meets bank scrutiny. Poorly prepared waybills are one of the most common causes of document rejection.

The before shipment phase is more than just paperwork; it is the exporter’s opportunity to prevent future disputes and delays. By finalizing the contract carefully, booking inspections on time, applying early for COO and PSC, and coordinating with a reliable carrier, exporters create a strong base for smooth shipment and timely payment. As the saying goes, “well begun is half done” — in LC transactions, this stage truly determines success.

2. During Shipment

Once all the groundwork has been laid in the before shipment stage — contract signed, inspection arranged, certificates applied for, and logistics confirmed — the exporter moves to the most crucial part: physically dispatching the goods. This stage generates the primary transport document (the truck waybill/consignment note), which is one of the most important requirements under a Letter of Credit (LC). Without accurate dispatch documentation, even perfectly inspected goods may not result in payment.

Let’s break down the three essential steps: Loading Goods, Transport Documentation, and Border Movement.

- Loading Goods

The journey begins at the exporter’s warehouse or cold storage facility, usually located near the border for perishable goods like tomatoes, onions, or other fresh vegetables. Proper packaging, labeling, and handling are critical here.

- Export-Standard Packaging: Produce must be packed in strong, ventilated cartons, crates, or bags that comply with both Indian export norms and Bangladeshi import standards. This ensures the goods remain fresh during transport.

- Labeling: Packages should clearly display product details, weight, and origin. Consistency in labeling reduces delays at customs and inspection points.

- Handling Practices: Workers should be trained to load carefully, avoiding damage to cartons or crates. Since fresh produce is sensitive to temperature and pressure, mishandling at this stage can cause significant losses.

At this point, exporters should also verify that the goods being loaded match the details on the commercial invoice and packing list. Any mismatch between the documents and the actual shipment can later lead to bank discrepancies.

- Transport Document (Truck Waybill/Road Consignment Note)

Once the goods are loaded, the carrier (usually a cross-border trucking company) issues a truck waybill or road consignment note. This document is the backbone of the LC compliance process, as it serves as proof of dispatch from the seller’s warehouse to the buyer’s warehouse across the border.

An LC-compliant transport document must include the following details:

- Description of Goods – Must match the LC wording exactly (e.g., “Fresh Tomatoes, HS Code 0702”).

- Quantity – Should match invoice and packing list, within the ±10% tolerance if allowed.

- Truck Number/Vehicle Identification – The exact registration number of the truck transporting the goods.

- Freight Terms – Must clearly state “Freight Prepaid” if that is required in the LC.

- Consignee Details – The importer’s details, exactly as mentioned in the LC.

- LC Reference Number – This must be typed or printed on the document, not handwritten.

- Dispatch Date – Proof that shipment occurred within the latest shipment date allowed under the LC.

If even one of these elements is missing or misstated, the issuing bank may raise a discrepancy and withhold payment until corrected. Exporters must therefore carefully check the waybill before the truck leaves the warehouse.

Best practice: Keep at least three signed originals and multiple copies of the waybill, as banks often require an original set for presentation.

- Border Movement (India → Bangladesh)

Once the waybill is issued, the truck proceeds to the Indian border point (e.g., Ghojadanga) for customs clearance. At this stage:

- Indian Customs verifies export documentation, including the invoice, packing list, COO, PSC, and waybill.

- The goods are inspected, and export clearance is granted.

The truck then crosses into Bangladesh via Bhomra Land Port, where import procedures begin. On the Bangladeshi side:

- Customs Authorities check the documents against import regulations.

- The consignee or their clearing agent completes local formalities, including payment of duties or taxes (if applicable).

For smooth clearance, it is critical that all documents — invoice, packing list, inspection certificate, COO, PSC, and waybill — are consistent and error-free. Any discrepancy at the border may cause delays, fines, or even rejection of the consignment.

Why This Stage is Critical

The During Shipment stage does more than just move goods from one point to another. It generates the primary transport document (waybill/consignment note), which the bank relies on to confirm that the exporter fulfilled their delivery obligations. Without this document, the bank cannot process payment under the LC.

For perishable goods, speed and accuracy are equally important. A delay of even one or two days at the border can reduce the freshness and market value of vegetables, impacting both the buyer and the exporter. That’s why exporters must ensure:

- The carrier is reliable and experienced in cross-border trade.

- All supporting documents are prepared in advance.

- Communication with the importer’s clearing agent is maintained for smooth handover at the destination.

The During Shipment stage is where all planning comes to life. From loading goods in export-standard packaging to obtaining an accurate waybill and clearing customs at Ghojadanga and Bhomra, every step must be executed with precision. This stage not only ensures physical delivery but also generates the key documentary proof that guarantees payment under the LC.

By carefully supervising loading, verifying transport documents, and preparing for border formalities, exporters can reduce risks, protect product quality, and move confidently to the after-shipment stage, where final documentation is assembled for bank presentation.

3. After Shipment – Assembling the Evidence Package

Once the goods have been dispatched, the exporter’s focus shifts from logistics to documentation. Under a Letter of Credit (LC), payment does not depend on whether the goods arrive safely or whether the buyer is satisfied — it depends entirely on the accuracy, consistency, and timeliness of the documents. This stage is critical because even small mistakes can cause banks to raise discrepancies, delaying or blocking payment.

- Preparing the Commercial Invoice & Packing List

The first documents an exporter must prepare are the Commercial Invoice and the Packing List.

- Commercial Invoice: This is the financial backbone of the shipment. It must show all details exactly as per LC, including:

- LC number and date.

- Exporter and importer’s name and address (word-for-word).

- HS Code and ITC Code.

- Product description, grade, and specification.

- Quantity and unit price.

- Total invoice value in the LC currency (usually USD).

- Terms of delivery (e.g., CPT, CIF).

- Packing List: This is the shipment’s blueprint. It lists:

- Package numbers and markings.

- Gross weight, net weight, and number of cartons.

- Dimensions of packages (if required).

- Confirmation that goods are packed to export standards.

Why it matters: Even minor differences — for example, invoice says “Fresh Tomatoes” but packing list says “Tomatoes” can lead to discrepancies. Best practice is to prepare both documents side by side, copying product descriptions directly from the LC.

- Collecting Mandatory Certificates

Next, the exporter gathers all certificates required under the LC.

- Inspection Certificate: Issued by an independent inspection agency (SGS, Intertek, Bureau Veritas). It certifies that goods meet quality and quantity requirements. The wording must match the LC exactly.

- Certificate of Origin (COO): Proves the goods are produced in India. Issued by Chambers of Commerce or Export Promotion Councils. Essential for customs and tariff benefits.

- Phytosanitary Certificate (PSC): Issued by the Plant Quarantine Authority of India. Mandatory for fresh agricultural exports, confirming produce is pest-free.

- Bank Authentication (SWIFT Confirmation): Some LCs require the issuing bank to confirm inspection or delivery authorization before payment. If this clause exists, exporters must ensure the bank provides it on time.

Why it matters: The certificates act as independent proof that the shipment is compliant with trade, health, and customs standards. A missing certificate or one issued after shipment when the LC requires “before shipment” is a common reason for bank rejection.

- Assembling the Document Package

Once all documents are ready, the exporter must assemble them into a single, complete set. Typical package includes:

- Commercial Invoice.

- Packing List.

- Transport Document (Waybill/Consignment Note).

- Inspection Certificate.

- COO.

- PSC.

- Insurance Certificate (if required).

- Bank Authentication / SWIFT confirmation (if required).

Each document must be:

- Consistent with the LC wording.

- Signed and stamped where applicable.

- Dated within the LC timelines.

Exporters should prepare at least two complete original sets: one for submission to the bank and one as a backup in case originals are lost in courier.

- Document Submission to the Bank

After shipment and preparation of documents, the final and most decisive stage in a Letter of Credit (LC) transaction is submitting the document set to the negotiating bank. This step determines whether the exporter receives timely payment or faces costly delays.

-

- Presentation Period

Most LCs specify a document presentation period, commonly 21 days from the shipment date, within which exporters must submit documents. Missing this deadline makes the LC invalid. However, experienced exporters never wait until day 21. Instead, they aim to submit documents within 5–7 days of shipment.

- Why early submission matters: If the bank finds errors (like a missing LC number or inconsistent quantities), the exporter still has time to correct and resubmit before the deadline. Submitting late leaves no room for correction, often leading to non-payment.

- LC Expiry Date

The LC itself has a final expiry date, which is separate from the presentation period. Even if the exporter submits documents within 21 days, if this falls after the LC expiry, the bank will not honor payment. For example, if the LC expires on 30th September, all compliant documents must be presented before this date. Exporters must therefore track both the shipment deadline and the LC expiry date.

- Bank’s Role in the Process

Once documents are submitted, the negotiating bank performs a compliance check. The bank compares every document against LC terms: product description, weights, prices, certificate dates, consignee details, and more.

- If compliant: The bank forwards documents to the issuing bank, which releases payment “at sight” (within 2–5 days) or after the deferred credit period (e.g., 30, 60, or 90 days).

- If discrepancies exist: The bank issues a discrepancy report. Exporters may correct documents (if time allows) or seek the importer’s written approval to accept the documents as-is.

- Why It Matters

Late or incomplete document submission is one of the most common reasons for non-payment under LC. Exporters often focus on shipping the goods but underestimate the strictness of bank timelines. An otherwise perfect shipment can fail financially if documents are submitted even a day late.

- Best Practices to Avoid Errors

- Use Templates: Create LC-compliant templates for invoices, packing lists, and certificates.

- Pre-Check with Bank: Some banks offer pre-check services before final submission.

- Digital Copies: Scan and keep digital records of all documents.

- Cross-Check: Verify each document against LC wording line by line.

- Submit Early: Never wait until day 21; aim for day 5–7.

4. Payment

The payment stage is the final and most critical part of an LC transaction. This is where all the effort of preparing, shipping, and assembling documents translates into actual money being credited to the exporter’s account. While it sounds simple — “submit documents, get paid” — in reality, banks apply strict checks, and even minor errors can cause delays, rejections, or unexpected charges. Understanding this stage in detail helps exporters secure timely, discrepancy-free payments.

1. Compliance Check

When the exporter submits the document set to their negotiating bank (also called the presenting bank), that bank forwards the documents to the issuing bank. The issuing bank’s job is not to inspect the goods themselves but to examine the documents against the exact wording of the LC.

This process is called the compliance check or document examination.

- Strict Matching: Banks operate under the principle of “strict compliance.” This means the documents must match the LC terms word-for-word and figure-for-figure.

- Key Elements Checked:

Invoice – Matches product description, quantity, HS code, unit price, and LC number.

- Packing List – Matches invoice and LC wording on packaging details.

- Transport Document (Waybill/Consignment Note) – Shows correct dispatch date, truck number, consignee, freight prepaid, and LC reference.

- Certificates (COO, PSC, Inspection Certificate) – Issued by authorized bodies, with dates and contents aligning with LC terms.

- Presentation Period – Documents must be presented within the timeframe specified (commonly 21 days from shipment).

If everything is correct, the issuing bank immediately authorizes payment under an at sight LC. This usually means the exporter’s bank credits funds within a few working days, depending on international settlement timelines.

2. Discrepancies in LC Transactions

Even though a Letter of Credit (LC) is designed to guarantee payment, exporters often face hurdles when their documents do not strictly comply with LC requirements. These mismatches are called discrepancies, and they are one of the most common reasons for delayed or rejected payments. Since banks deal only with documents, not goods, even a small clerical error can cause major problems.

Common Types of Discrepancies

- Missing LC Number on Documents

Every key document — invoice, packing list, transport document — must mention the LC number. If missing, the bank considers it incomplete.

- Inconsistent Quantity

For example, if the invoice states 500 MT of tomatoes but the packing list shows 495 MT, the bank sees this as a mismatch, even if the physical goods shipped are correct.

- Transport Document Errors

If the truck waybill does not mention the vehicle number, freight prepaid note, or consignee details exactly as in the LC, it becomes non-compliant.

- Date Errors

Shipments made after the latest shipment date in the LC, or documents issued outside the allowed time frame (e.g., beyond 21 days), are treated as discrepancies.

- Spelling and Wording Issues

Even simple differences matter. If the LC requires “Fresh Tomatoes” and the invoice says “Tomatoes,” banks may reject the set.

- Certificates Not Matching Timing

Some LCs require inspection or phytosanitary certificates before shipment. If issued later, they may not be accepted.

Bank Actions on Discrepancies

When discrepancies are detected, the issuing bank issues a discrepancy report. The exporter then has two options:

- Correct and Resubmit: If time allows, the exporter can fix the errors and present revised documents.

- Seek Importer’s Approval: The bank asks the buyer whether they are willing to accept the documents despite discrepancies. If the buyer agrees in writing, payment proceeds. If the buyer refuses, the bank will not release funds.

Costs and Risks of Discrepancies

Most LCs specify a discrepancy fee, often around USD 150 per set of documents. This fee is charged to the exporter and reduces profit margins. More importantly, discrepancies cause payment delays, which can create cash flow pressure, especially for exporters of perishable goods who rely on quick turnover.

Best Practices to Avoid Discrepancies

- Double-check every document against LC wording before submission.

- Train staff on LC compliance and use professional freight forwarders.

- Present documents early, leaving time to correct errors if needed.

- Use templates aligned with LC requirements for invoices, packing lists, and waybills.

In short: Discrepancies are preventable. Attention to detail, early preparation, and strict alignment with LC terms can save exporters both money and time, ensuring smooth and timely payment.

3. Payment Release

Once the issuing bank has examined the documents and found them to be in strict compliance with the LC terms, the process of releasing payment begins. This stage is the final reward for the exporter’s careful preparation and documentation.

The steps are straightforward but highly structured:

- Authorization: The issuing bank communicates its acceptance by sending a SWIFT message (usually MT 740/742/754 depending on the flow) to the negotiating or advising bank. This message confirms that the documents are in order and that the payment obligation will be honored.

- Settlement: Following authorization, the issuing bank arranges the actual fund transfer. Settlement typically occurs through international banking channels in USD, unless another currency was agreed upon. This involves correspondent banks if the issuing and negotiating banks do not have a direct relationship.

- Credit to Exporter: Once the negotiating bank receives the funds, it credits the exporter’s account. At this point, the trade cycle is officially complete — the goods have been shipped, the documents verified, and the payment delivered.

In most cases, under an at sight LC, exporters receive payment within 2–5 business days after compliance confirmation. This ensures exporters can quickly recycle working capital into new shipments. In the case of a deferred payment LC, the timeline shifts according to the agreed terms, such as 30, 60, or 90 days after shipment.

For exporters, timely and accurate documentation is the key to ensuring smooth payment release without delays or additional costs.

4. Why Accuracy Matters

In an LC transaction, exporters must always remember a crucial principle: banks deal only with documents, not with goods. This means that even if the shipment reaches the buyer in perfect condition and the importer is satisfied, the bank can still refuse payment if the supporting documents do not comply with the LC terms.

For example, if an LC requires the phrase “Fresh Tomatoes, HS Code 0702.00” on every document, but the invoice only states “Tomatoes,” the bank may treat this as a discrepancy, regardless of whether the goods are exactly what the buyer ordered. Similarly, if the truck waybill misses the LC number or shows a slightly different weight, the issuing bank can hold back payment until corrections are made.

To avoid such costly errors, exporters must adopt a strict accuracy-first approach:

- Double-check every document against the LC wording before submission. Even small spelling or numbering differences can cause rejection.

- Use experienced freight forwarders and inspection agencies who understand LC compliance and can issue documents correctly.

- Submit documents early, ideally within a week of shipment, leaving enough time to fix mistakes if the bank raises queries.

- Keep clear communication with the buyer, as in some cases, the importer’s written approval is needed to accept minor discrepancies.

Ultimately, accuracy in documentation is not just about avoiding fees or delays — it is the exporter’s safeguard for guaranteed payment under the LC.

The timeline of an LC transaction is structured but unforgiving. Success depends on discipline and accuracy. Exporters who plan carefully — securing inspections, preparing documents in advance, double-checking every detail, and submitting early — achieve smooth payments without discrepancies. For perishable exports like vegetables, where timing and cash flow are critical, mastering this timeline ensures both trade security and financial stability.

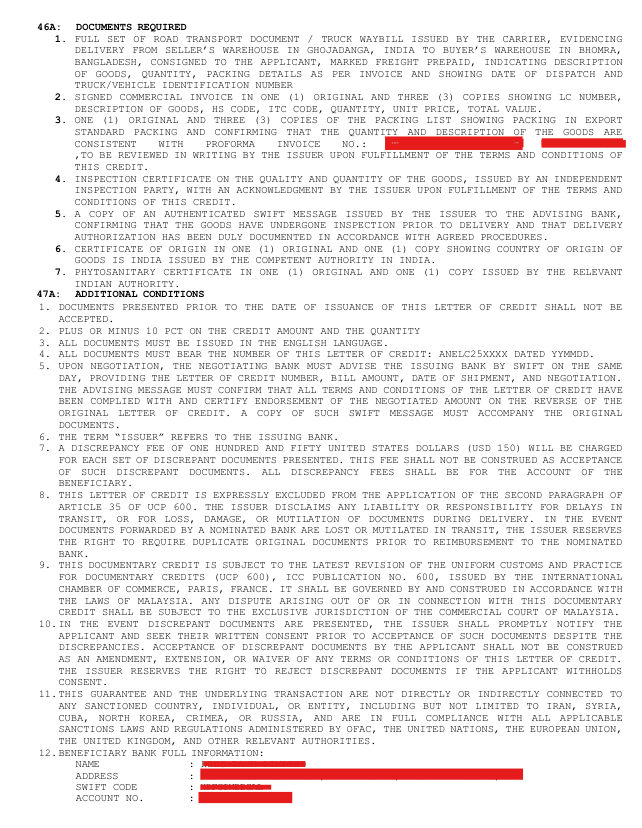

Complete List of Documents Required Under an Export LC (Agricultural Exports: India → Bangladesh)

When working under a Letter of Credit (LC), exporters must remember: payment is guaranteed only if documents match LC terms 100%. Beyond the core documents (invoice, packing list, COO, PSC, waybill), many LCs also demand additional certificates depending on product type, trade regulations, or buyer’s requirements.

1. Transport Document (Truck Waybill / Road Consignment Note)

- Issued by: Carrier (truck operator/logistics company).

- Purpose: Proof of dispatch from exporter’s warehouse to importer’s location.

- Key Requirements: Must state LC number, consignee details, description of goods (matching LC wording), packing, dispatch date, truck number, and “Freight Prepaid.”

- Common Mistakes: Missing truck number, wrong consignee name, or incorrect freight notation (“Collect” instead of “Prepaid”).

2. Commercial Invoice

- Issued by: Exporter.

- Purpose: The financial backbone of the trade.

- Key Requirements: Must show LC number, HS Code, ITC Code, product description (exact LC wording), quantity, unit price, total value, and currency. Signed and stamped.

- Common Mistakes: Spelling mismatches (e.g., “Tomatoes” vs. “Fresh Tomatoes”), unsigned invoices, or wrong HS code.

3. Packing List

- Issued by: Exporter.

- Purpose: Shipment breakdown for customs and buyer.

- Key Requirements: Package numbers, marks/labels, gross and net weights, dimensions, and confirmation of export-standard packing.

- Common Mistakes: Quantity/weight not matching invoice, missing package numbers.

4. Inspection Certificate

- Issued by: Independent agencies (SGS, Intertek, Bureau Veritas, Cotecna).

- Purpose: Confirms goods meet agreed quality and quantity standards.

- Key Requirements: Must reference LC number and use exact wording (e.g., “Quality and Quantity certified as per Proforma Invoice No. X”).

- Common Mistakes: Vague language (“goods found satisfactory”), missing LC reference, certificate issued after shipment when LC requires before.

5. Bank Authentication (if required)

- Issued by: Issuing bank (via SWIFT).

- Purpose: Confirms inspection/delivery authorization was completed.

- Common Mistakes: Exporters forgetting this condition, leading to rejection at the issuing bank.

6. Certificate of Origin (COO)

- Issued by: Authorized Indian Chambers of Commerce / Export Promotion Councils.

- Purpose: Proves goods were produced in India. Sometimes required for tariff benefits under trade agreements.

- Common Mistakes: COO issued by unauthorized bodies, wrong HS code, exporter name mismatch.

7. Phytosanitary Certificate (PSC)

- Issued by: Plant Quarantine Authority of India (PQAI).

- Purpose: Confirms produce is free from pests and diseases, mandatory for fresh vegetables/fruits.

- Common Mistakes: PSC dated after shipment, missing product details, delayed issuance blocking customs clearance.

Additional Documents Often Required in Agricultural LCs

8. Insurance Certificate

- Issued by: Exporter’s insurer.

- When Required: If Incoterm is CIF or CIP.

- Purpose: Proves shipment is insured against loss or damage.

- Common Mistakes: Forgetting to include LC number, wrong coverage period.

9. Fumigation Certificate

- Issued by: Authorized fumigation agencies.

- When Required: For onions, garlic, pulses, or wooden-packaged products.

- Purpose: Confirms goods/packaging were fumigated to kill pests.

- Common Mistakes: Certificate not issued before shipment, or fumigation not recognized by Bangladesh customs.

10. Weight Certificate

- Issued by: Independent weighbridge or inspection agency.

- When Required: For bulk commodities like onions or potatoes.

- Purpose: Certifies weight shipped matches invoice/packing list.

- Common Mistakes: Weight variation beyond ±10% tolerance.

11. Quality / Analysis Certificate

- Issued by: Accredited labs (e.g., NABL in India).

- When Required: For products needing chemical/purity checks (spices, chilies, turmeric).

- Purpose: Confirms compliance with buyer’s specifications (moisture, pesticide levels, etc.).

- Common Mistakes: Using unrecognized labs, missing LC wording.

12. Sanitary / Health Certificate

- Issued by: FSSAI or recognized authorities.

- When Required: For processed foods or frozen produce.

- Purpose: Confirms goods are safe for human consumption.

- Common Mistakes: Late issuance, or missing details about batch numbers.

13. Export Declaration (SDF – Statutory Declaration Form)

- Issued by: Exporter via DGFT/Authorized Bank.

- Purpose: RBI compliance, confirming proceeds will be realized.

- Note: Usually not part of LC presentation but mandatory in India for regulatory clearance.

14. Customs Bill of Export / Shipping Bill

- Issued by: Indian Customs.

- Purpose: Proof of legal export clearance.

- Note: Typically, not required by the foreign bank, but necessary for Indian banking compliance.

15. Import Permit (Bangladesh side, if applicable)

- Issued by: Bangladeshi authorities.

- When Required: For restricted or controlled products (e.g., onions during shortage, rice).

- Purpose: Confirms buyer has government permission to import.

- Common Mistakes: Exporters not verifying if buyer’s permit is valid and active.

Key Industry Insight

- Every LC is unique: The required documents vary depending on the buyer’s conditions, product type, and bilateral regulations.

- Common Rule: All documents must be consistent, accurate, and within deadlines.

- Best Practice: Exporters should create a document compliance checklist for each LC before shipment.

Key Conditions Exporters Must Watch

When exporting under a Letter of Credit (LC), exporters often focus on shipping the goods and overlook the finer details of documentation. However, in LC transactions, banks are not concerned with the physical goods — they only examine the documents. This makes compliance with LC conditions absolutely essential. Even a minor deviation can result in discrepancies, leading to delays, added charges, or even non-payment.

Here are the most critical conditions exporters must pay close attention to:

1. Exact Match Rule

The golden principle of LC transactions is strict compliance. This means that every word, figure, and detail in the documents must match the LC exactly.

- Example: If the LC specifies “Fresh Tomatoes, HS Code 0702.00,” then the invoice, packing list, and transport document must carry the same description. If one document only says “Tomatoes,” banks may reject it.

- Why It Matters: Banks do not interpret or assume; they check line by line. Even small spelling errors, abbreviations, or differences in punctuation can lead to discrepancies.

Tip: Always prepare templates based on LC wording and copy text directly to avoid inconsistencies.

2. Language

Most LCs clearly state that all documents must be in English. This requirement eliminates ambiguity, ensures international readability, and avoids translation disputes.

- Common Mistake: Carriers or inspection agencies sometimes issue waybills or certificates in the local language. If not in English, the bank may refuse them.

- Solution: Instruct all third parties — transporters, inspection agencies, and chambers of commerce — to issue documents in English. If bilingual, English must be the dominant version.

3. LC Reference

Every document must carry the LC number and date. This helps banks connect the documents to the correct transaction.

- Example: If the LC number is ANE12345 dated 01-09-2025, all documents must repeat this detail in the header or footer.

- Why It Matters: If even one document is missing the LC reference, banks may claim it is not linked to the LC, creating unnecessary delays.

Tip: Always make the LC number a mandatory field in your invoice, packing list, and waybill templates.

4. Deadlines

Time is a critical factor in LC transactions. Exporters must comply with two key deadlines:

- Latest Shipment Date – Goods must be shipped before this date. Even one day late will lead to non-compliance.

- Presentation Period – Documents must be submitted to the bank within a fixed number of days after shipment, usually 21 days, but always before the LC expiry date.

- Example: If shipment takes place on 1st September and the LC allows 21 days, documents must be presented by 22nd September or earlier.

- Why It Matters: Late presentation is one of the most common discrepancies.

Tip: Present documents within 5–7 days of shipment, leaving time to correct errors if necessary.

5. Partial Shipments

Some LCs allow partial shipments, while others prohibit them. Exporters must check this clause carefully.

- If Allowed: Goods can be shipped in multiple consignments, each with its own set of documents. This is useful for large agricultural shipments spread over several trucks.

- If Not Allowed: Exporters must send the full quantity in a single shipment. Dividing the load into multiple trucks (with separate waybills) may be treated as non-compliance.

Tip: Clarify this condition during contract negotiation to avoid costly surprises later.

6. Charges

Banks often impose a discrepancy fee if documents are not compliant. This fee is usually around USD 150 per set of documents.

- Impact: While USD 150 may not sound huge, repeated discrepancies across multiple shipments can quickly erode profit margins.

- Cash Flow Stress: Beyond the fee, discrepancies delay payment. For exporters handling perishable goods, even a few days’ delay can impact working capital.

Tip: Treat discrepancy fees as avoidable losses. Invest in training your staff or using professionals who specialize in LC documentation.

Exporting under an LC is secure but unforgiving. Banks will only release payment if the documents are perfectly accurate and submitted on time. Exporters must therefore pay close attention to six key conditions: the exact match rule, English-only documents, inclusion of LC references, strict deadlines, rules on partial shipments, and the risk of discrepancy charges.

By adopting a disciplined approach — using standardized templates, double-checking every document, and presenting early — exporters can achieve zero discrepancies. This not only ensures timely payment but also builds credibility with buyers and banks, paving the way for smoother trade in the future.

Step-by-Step Compliance Checklist

A Letter of Credit (LC) is one of the safest payment mechanisms in international trade, but its success depends entirely on documentation accuracy. To avoid discrepancies and ensure timely payment, exporters should follow a structured compliance checklist.

1. Confirm LC Terms with Buyer Before Shipment

Before shipping, exporters must carefully review the draft LC against the sales contract. Any mismatch in product description, HS code, Incoterm, packing standards, or shipment deadlines should be corrected immediately. It is always easier to amend the LC before shipment than to deal with discrepancies after documents are submitted.

2. Book Inspection Early to Avoid Delays

If the LC requires an independent inspection (e.g., from SGS or Intertek), book it well in advance. Inspection agencies may need time to visit the warehouse, check the goods, and issue certificates. Delaying this step can hold back the shipment and disrupt the entire schedule.

3. Apply for COO and PSC in Advance

- Certificate of Origin (COO): Proves the goods are produced in India, issued by Chambers of Commerce or Export Promotion Councils.

- Phytosanitary Certificate (PSC): Confirms goods are pest- and disease-free, issued by the Plant Quarantine Authority.

Both documents are mandatory for agricultural trade and must be applied for early to avoid border clearance delays.

4. Double-Check Carrier’s Waybill for Accuracy

The transport document is one of the most scrutinized. Ensure the waybill shows the LC number, dispatch date, truck number, consignee details, freight prepaid note, and exact product description. Missing any of these details can cause a bank to reject the document set.

5. Prepare Invoice & Packing List Using LC Wording

Every detail on the invoice and packing list — including product description, HS code, unit price, and total value — must match the LC exactly. Exporters should copy wording directly from the LC to prevent spelling or phrasing discrepancies.

6. Assemble All Documents in One Set for the Bank

Compile the invoice, packing list, inspection certificate, COO, PSC, waybill, and any required bank confirmations into a single set. Numbering and indexing the documents helps banks process them faster.

7. Submit Early (Within 5–7 Days After Shipment)

Although most LCs allow 21 days from shipment for document presentation, exporters should aim to submit within a week. Early submission gives time to fix errors if the bank raises queries and ensures faster payment release.

Best Practices for Smooth LC Payments

Getting paid under a Letter of Credit (LC) is not just about shipping the goods — it’s about documentary compliance. Exporters must think like bankers, ensuring every document is exact, consistent, and timely. The following best practices help exporters minimize risk, avoid discrepancies, and secure faster payments.

1. Aim for Zero Discrepancies by Following LC Text Word-for-Word

The most common reason for delayed payments is mismatched documentation. Banks apply a principle of strict compliance, meaning even minor differences are treated as errors. For example, if the LC requires “Fresh Tomatoes, HS Code 0702.00.19,” and the invoice only says “Tomatoes,” the bank may reject the set. Exporters should copy product descriptions, codes, and terms exactly as written in the LC.

2. Always Submit Early to Avoid Missing Deadlines

Most LCs give exporters 21 days from the shipment date to submit documents. Waiting until the last moment increases the risk of late submission, especially if corrections are needed. A best practice is to submit within 5–7 days of shipment. Early submission gives exporters time to fix errors, ensures faster compliance checks, and secures quicker payments.

3. Use Professional Inspection Agencies to Ensure Acceptance

Independent inspection certificates are often mandatory in agricultural exports. Using internationally recognized agencies such as SGS, Intertek, or Bureau Veritas ensures credibility and bank acceptance. These agencies also understand LC requirements, so their certificates are less likely to trigger discrepancies.

4. Avoid Handwritten Corrections — Use Clean, Typed Documents

Banks prefer clear, professional documents. Handwritten corrections, overwriting, or manual adjustments raise doubts about authenticity. Instead, exporters should prepare all documents electronically, use standard templates, and double-check for errors before printing and signing. A clean document set signals professionalism and reduces the risk of rejection.

5. Keep a Backup Set of Documents in Case Originals Are Lost

Since banks often require original documents, losing them in transit can create serious delays. A smart practice is to prepare duplicate originals and keep a backup set ready. If the courier loses the first set, exporters can quickly submit the backup without jeopardizing payment timelines.

Common Mistakes Exporters Should Avoid

Even experienced exporters sometimes make avoidable mistakes when working under a Letter of Credit (LC). Since banks deal only with documents, not the actual goods, these errors can cause payment delays, discrepancy charges, or outright rejection. Below are the most common pitfalls and how to avoid them.

1. Forgetting to Put LC Number/Date on Documents

Every key document — invoice, packing list, transport document, inspection certificate — must carry the LC number and date. Without this, the bank may claim the documents are unrelated to the LC.

Example: An exporter submits a packing list without the LC reference. The bank rejects it, even though the shipment was correct.

Prevention: Build the LC reference into your document templates so it cannot be overlooked.

2. Mismatch Between Invoice and Packing List

The invoice and packing list must be consistent in terms of product description, quantity, weight, and packaging.

Example: Invoice shows 500 MT of onions, but packing list shows 495 MT. Even though the goods shipped are correct, the bank sees this as a discrepancy.

Prevention: Cross-check documents side by side before submission.

3. Missing Details on Waybill

The waybill or road consignment note is often the most scrutinized document. If details like truck number, freight prepaid note, consignee details, or LC number are missing, banks may reject it.

Prevention: Instruct carriers clearly and review the waybill before trucks leave the warehouse.

4. Submitting Documents Late to the Bank

Most LCs allow 21 days from shipment date for document presentation. Submitting late makes the LC invalid, even if goods were shipped correctly.

Prevention: Aim to submit within 5–7 days of shipment to leave room for corrections.

5. Adding Unnecessary Information

Sometimes exporters add extra details not required in the LC, which can conflict with the LC wording.

Example: LC states “Fresh Tomatoes,” but exporter adds “Grade A, Farm XYZ” in the invoice. The bank may reject this as inconsistent.

Prevention: Stick strictly to LC terms. Do not add or modify details unless required.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Q1. What happens if the shipment date on the transport document is later than the “latest shipment date” in the LC?

Every LC specifies a latest shipment date, which acts as a strict deadline. If the transport document (like a truck waybill) shows a dispatch date later than this, the bank will classify it as a discrepancy. Even if the goods were shipped and the buyer has received them, the bank is bound by LC rules and cannot honor payment without compliance. In such cases, the exporter has two options: request the buyer to accept the late shipment or amend the LC before shipment. If the buyer agrees in writing, the bank may release funds, but until then, the payment remains blocked. Exporters must always plan shipments a few days before the last date to account for delays in loading, inspection, or customs clearance. Late shipments are among the most common reasons for LC payment disputes.

Q2. Can handwritten corrections on documents be accepted under LC?

Banks prefer documents that are clean, typed, and free of manual alterations. Handwritten corrections create doubts about authenticity and accuracy, especially in legal and financial instruments. For example, if an invoice shows “500 MT” and this is manually corrected to “450 MT” with a pen, banks may reject the document because it looks tampered. If corrections are unavoidable, they must be countersigned, stamped, and initialed by the issuing authority (e.g., the exporter, chamber, or carrier). However, even with signatures, some banks may still treat them as discrepancies. The safest approach is to avoid manual changes altogether — instead, reissue a fresh, corrected document. Exporters should maintain editable templates for invoices, packing lists, and waybills, so mistakes can be corrected digitally before submission. This practice prevents disputes and saves time. In LC compliance, presentation quality is just as important as accuracy.

Q3. If an LC is “available with any bank by negotiation,” what does that mean for the exporter?

Normally, an LC is made available only with a specific advising or nominated bank. However, when an LC states it is “available with any bank by negotiation,” it gives exporters more flexibility. In this case, the exporter can submit documents to any bank of their choice for negotiation, rather than being tied to one institution. This is particularly useful if the exporter has a trusted relationship with a local bank or if their regular bank offers faster processing. However, even if documents are negotiated by another bank, they must still be forwarded to the issuing bank for final settlement. The exporter should also note that negotiation charges may vary depending on the bank chosen. While this flexibility is beneficial, exporters must ensure the negotiating bank is experienced in LC handling to avoid mistakes that could delay payment.

Q4. Can banks reject documents if the exporter’s name is slightly different from the LC (e.g., Pvt. Ltd. vs Private Limited)?

Yes. Even minor variations in the exporter’s (beneficiary’s) name can trigger a discrepancy. For example, if the LC states “Nafee Exim Global Private Limited” but the invoice mentions “Nafee Exim Global Pvt. Ltd.”, banks may treat them as two different legal entities. This strictness exists because LCs are legal contracts, and banks must ensure that payment is made only to the exact beneficiary mentioned. Exporters should therefore ensure that their company name, address, and registration details appear consistently across all documents: LC, invoice, packing list, certificates, and waybill. The safest approach is to use the same spelling and format as in the LC, even if it differs slightly from local business usage. Before finalizing the LC, exporters must request corrections in case of name errors. Otherwise, they risk delays or non-payment due to technical discrepancies.

Q5. What if the goods are shipped in multiple trucks but the LC prohibits partial shipments?

If an LC explicitly prohibits partial shipments, the entire consignment must be dispatched in a single lot with one consolidated transport document. For example, if the LC calls for 500 MT of tomatoes, and the exporter dispatches 300 MT in one truck and 200 MT in another (with separate waybills), this will be considered a partial shipment. The bank will raise a discrepancy, even if the importer has received the goods in full. To comply, exporters must coordinate with logistics providers to ensure all goods leave together, ideally on one vehicle or under one combined document. If logistical or operational reasons require multiple trucks, exporters should negotiate with the buyer in advance to have the LC amended to allow partial shipments. Ignoring this clause can result in delayed or withheld payments. In LC compliance, shipment structure is just as critical as documentation wording.

Q6. What happens if the COO or PSC is dated after the shipment date?

A Certificate of Origin (COO) and Phytosanitary Certificate (PSC) are often required by the LC before shipment to prove goods’ authenticity and phytosanitary safety. If these certificates are dated after shipment, banks may raise discrepancies because it appears the goods were dispatched without compliance. For example, if a truck leaves on 1st October but the PSC is dated 3rd October, the issuing bank may refuse documents. While the importer may still accept the shipment, the exporter risks payment delay. The solution is to coordinate early with the issuing authorities — apply for PSC and COO in advance so that inspections and approvals are completed before loading and dispatch. Exporters must also check LC wording carefully: some allow certificates dated “on or before shipment,” while others specify “prior to shipment.” These small details decide whether payment flows smoothly or gets blocked.

Q7. What is the impact of presenting documents after the 21-day presentation period?

Most LCs allow exporters a maximum of 21 days from shipment date to present documents to the negotiating bank. Submitting after this period makes the documents stale, and the LC becomes invalid, even if the goods have already arrived. For example, if goods are shipped on 1st September, the full set of documents must be presented by 22nd September or earlier. If missed, the exporter can only get paid if the importer explicitly approves the late documents — which carries risk and causes delays. The best practice is to submit documents within 5–7 working days after shipment. This not only ensures compliance but also leaves time to fix discrepancies if banks raise queries. Exporters handling perishable goods must be even more vigilant, since delayed document presentation can impact both payment timelines and buyer trust. Timeliness in document presentation is as important as accuracy.

Q8. Can exporters submit documents electronically under an LC?

Traditionally, LCs require original paper documents, such as signed invoices, stamped packing lists, and certified certificates. However, with growing digitization, the ICC introduced eUCP (Electronic Uniform Customs and Practice) rules, which allow electronic submission of documents. Exporters can use platforms like Bolero, essDOCS, or TradeLens to transmit documents securely. That said, electronic documents are only acceptable if the LC explicitly mentions that it is subject to eUCP. If the LC does not specify this, banks will reject electronic files and insist on physical copies. Exporters should confirm document format requirements during contract negotiation and request eUCP clauses if digital submission is preferred. While electronic LCs speed up processing and reduce courier risks, they are still not universally accepted. Therefore, exporters must carefully check whether the buyer’s bank and their own negotiating bank are equipped to handle eUCP transactions.

Q9. What if the LC specifies “Freight Prepaid,” but the waybill says “Freight Collect”?

Freight terms are a critical part of LC compliance. If the LC specifies “Freight Prepaid”, it means the exporter is responsible for transport costs, and the waybill must clearly state that freight has already been paid. If the waybill instead says “Freight Collect,” it suggests the importer is responsible for payment at the destination. This creates a direct conflict with LC terms and will be flagged as a discrepancy. Banks do not interpret context — they only check wording. To avoid this, exporters must instruct their carriers and logistics providers in advance to issue documents exactly as per LC. A single mistake in freight notation can hold up thousands of dollars in payment. Exporters should double-check the waybill before the truck leaves. Ensuring consistency in transport terms is just as important as product description accuracy in LC compliance.

Q10. What if the exporter ships a slightly different product grade than specified in the LC?

Even if the buyer is satisfied with the goods, banks will reject payment if the product description in the documents does not match the LC. For example, if the LC specifies “Fresh Tomatoes, Grade A” but the invoice says “Fresh Tomatoes, Grade B”, banks consider this a mismatch. LCs are legal instruments that guarantee payment based on exact compliance, not on the actual goods delivered. This strict rule prevents disputes but can frustrate exporters who assume minor variations are acceptable. The solution is simple: exporters must ensure that the goods shipped, the product grade, and the wording in the documents mirror the LC description exactly. If the buyer wants a different grade or specification, the LC must be formally amended before shipment. Exporters should never assume that “buyer acceptance” overrides LC rules — banks only pay against documents, not buyer preferences.

Q11. Can exporters amend an LC after shipment?

No. Once goods have been shipped, the LC terms are locked. Any changes or corrections must be done before shipment and with the agreement of all three parties: the buyer (applicant), the issuing bank, and the exporter (beneficiary). For example, if the LC prohibits partial shipments but the exporter needs multiple trucks, this must be amended before goods are dispatched. After shipment, amendments are not valid because the LC represents a fixed contract. If exporters realize after shipment that their documents do not comply, they can only request the buyer to accept the discrepancies, but this is risky. Therefore, exporters must thoroughly review the LC immediately upon receipt and request amendments early if needed. Waiting until after shipment leaves them exposed to potential non-payment and weakens their negotiating position with the buyer and bank.

Q12. Why do banks charge a discrepancy fee?

Banks charge a discrepancy fee because handling non-compliant documents requires extra administrative work, manual corrections, and additional communication with the importer. Fees are typically around USD 100–150 per set of documents, though this may vary depending on the bank and country. These charges are deducted directly from the exporter’s payment, reducing profit margins. Beyond the financial cost, discrepancies also delay payment, which creates cash flow pressure, especially for exporters of perishable goods who need working capital quickly. Banks use these fees to encourage exporters to present accurate, compliant documents the first time. To avoid paying discrepancy charges, exporters should establish document verification protocols, train staff in LC compliance, and submit documents early to leave room for corrections. Treating discrepancy fees as a cost of doing business is dangerous; they are avoidable losses that reflect poor documentation practices.

Q13. What happens if the LC expires before document submission?

If an LC expires before the exporter submits documents, it becomes null and void. Banks have no obligation to honor payments after expiry, regardless of whether goods were shipped on time. For example, if the LC expires on 30th September, and documents are submitted on 1st October, the bank will not process them. The only solution is to request an extension of the LC from the importer before expiry. Exporters should monitor LC expiry dates closely and maintain internal reminders. In cases where shipment or documentation may be delayed, exporters must communicate early with buyers to request an extension. Once expired, an LC cannot be revived, leaving exporters dependent entirely on buyer goodwill for payment. For perishable goods, missing an LC deadline can mean financial disaster, so managing expiry timelines is as important as meeting shipment deadlines.

Q14. What if the importer’s name is misspelled on the invoice?

Banks require that the importer’s name and address on all documents match the LC exactly. Even small spelling differences, abbreviations, or formatting changes may be treated as discrepancies. For example, if the LC states “Khadiza Trading Corporation” but the invoice shows “Khadija Trading Co.”, banks may reject it. This strictness ensures that documents cannot be manipulated or linked to the wrong party. Exporters must carefully copy the importer’s details exactly as stated in the LC, even if the spelling seems unusual or inconsistent with local business usage. If the LC itself contains an error in the importer’s name, exporters should immediately request a correction from the buyer and issuing bank before shipment. Assuming that banks will ignore minor spelling, mistakes is risky — under LC rules, precision is non-negotiable.

Q15. Can exporters request advance payment under an LC?

Under a standard sight LC, payment is only released after shipment and document verification. However, exporters who require financing before shipment can use special LC types like Red Clause LCs and Green Clause LCs.

- Red Clause LC: Allows the exporter to receive advance payment before shipment against a simple undertaking, often for procurement or production costs.

- Green Clause LC: Provides advance payment against warehouse receipts and insurance documents, offering more security to banks.

These clauses must be agreed upon during contract negotiation and included in the LC text. While advance payment helps exporters manage cash flow, it comes with stricter documentation requirements and sometimes higher bank charges. Exporters must weigh the benefits of early financing against the added compliance costs. In most standard agricultural exports, buyers prefer sight LCs to reduce their risk exposure.

Q16. What if the inspection certificate does not carry the exact wording required in the LC?

LCs often specify the exact wording to be included in inspection certificates. For example, “Goods inspected and found in conformity with Proforma Invoice No. 123 dated 01-09-2025.” If the certificate says only “Goods inspected and found satisfactory,” banks may reject it because the wording does not match. This may seem overly strict, but banks are bound by documentary compliance rules. To avoid this, exporters must share the LC wording directly with the inspection agency and ensure it is copied word-for-word into the certificate. Agencies like SGS or Intertek are familiar with LC requirements, but smaller local agencies may overlook such details. Exporters should always review draft certificates before issuance to confirm compliance. A single missing phrase in the inspection certificate can block thousands of dollars in payment, making attention to wording critical.

Q17. Is insurance required under a CPT (Carriage Paid To) Incoterm in an LC?

No. Under CPT (Carriage Paid To), the exporter’s obligation is to pay for transportation to the agreed destination, but not for insurance. Insurance under CPT is the importer’s responsibility. If the LC requires insurance, then the agreed Incoterm should be CIF (Cost, Insurance, Freight) or CIP (Carriage and Insurance Paid To). Exporters must clarify this at contract negotiation to avoid unexpected costs. If an LC specifies CPT but also requires an insurance certificate, this is a contradiction, and the exporter should request an amendment before shipment. Exporters must always align Incoterms with LC requirements because inconsistencies can cause delays or disputes. For agricultural products, where risks like spoilage or damage are high, insurance may be wise even if not legally required. However, responsibility must be clarified clearly in the contract and LC.

Q18. What is the risk if multiple sets of originals are sent separately to the bank?

If original documents are split and sent separately, banks may misplace or mismatch them, creating discrepancies. For example, if an exporter sends the invoice and packing list first, and the transport document later, the issuing bank may treat them as incomplete. Best practice is to submit one complete, indexed set of documents in a single package. Exporters should also retain duplicate originals as backups in case of courier delays or loss. Splitting submissions increases the risk of confusion, especially when banks process high volumes of LC documents daily. To ensure smooth processing, exporters should use secure courier services, track document delivery, and confirm receipt with their negotiating bank. A well-organized, single-set submission signals professionalism and reduces risks of discrepancies or payment delays.

Q19. Can an LC be confirmed to reduce country risk?

Yes. A confirmed LC adds an extra layer of security for exporters. In addition to the issuing bank’s guarantee, a second bank (usually located in the exporter’s country) adds its own commitment to pay. This protects exporters against risks like the issuing bank’s insolvency, currency restrictions, or political instability in the buyer’s country. For example, if the issuing bank in Bangladesh defaults, the confirming bank in India or Singapore will still honor payment. However, confirmed LCs come with higher charges, which are usually borne by the exporter. Exporters dealing with new buyers, politically unstable markets, or unknown banks should request confirmed LCs to secure payment. This reduces risk but increases transaction costs. It’s a trade-off between safety and expense. For high-value or first-time transactions, confirmation is a smart strategy to ensure guaranteed payment.

Q20. What does “at sight” mean in LC?

An at sight LC means that once the exporter submits all documents and the issuing bank verifies them as compliant, payment is released immediately. In practice, this usually takes 2–5 working days depending on the banking channel. Unlike deferred payment LCs, there is no waiting period, the exporter gains quick access to funds. This is especially useful for perishable goods like vegetables, where exporters need fast payment to reinvest in procurement. Exporters should note that “at sight” does not mean instant cash; it still requires document examination, but it ensures payment without credit delays once compliance is confirmed.

Q21. Can I ship goods in parts under an LC?

Yes, but only if the LC explicitly allows partial shipments. If the LC permits partial shipments, exporters can divide goods across multiple trucks or consignments, each with its own transport document and document set. If the LC prohibits partial shipments, the full consignment must move in one lot. Shipping in parts when it is not allowed will create discrepancies, and banks may refuse payment. For bulk agricultural exports, where loading may require multiple trucks, exporters should always request an LC amendment allowing partial shipments. This gives flexibility while staying compliant. Checking this clause in advance avoids costly disputes.

Q22. Who issues a Certificate of Origin (COO)?

A Certificate of Origin (COO) is issued by authorized Indian trade bodies, such as Chambers of Commerce and Export Promotion Councils. It certifies that the goods were grown, produced, or manufactured in India, which is essential for customs clearance and for buyers to claim tariff benefits under trade agreements. Exporters must submit supporting documents like invoices, packing lists, and sometimes inspection reports to obtain the COO. Since it is often a mandatory LC requirement, exporters should apply early to avoid delays. Without a valid COO, customs clearance at the Bangladesh border may be slowed, and the bank may reject the document set.

Q23. Who issues a Phytosanitary Certificate (PSC)?

A Phytosanitary Certificate (PSC) is issued by the Plant Quarantine Authority of India (PQAI). It certifies that agricultural products are free from pests, diseases, or contamination. For perishable exports like tomatoes, onions, or chilies, this certificate is often a mandatory LC requirement and also essential for clearance at Bangladesh customs. The PQAI inspects the goods physically, usually at the warehouse or loading point, before issuing the certificate. Exporters should apply well in advance since last-minute delays in PSC issuance can block shipments. If a PSC is dated after shipment when the LC requires it before, banks may treat it as a discrepancy, delaying payment.

Q24. What happens if documents have small errors?

Even small errors like spelling mistakes, missing LC numbers, inconsistent weights, or wrong dates can lead to discrepancies. Banks operate on a strict compliance rule, so they do not overlook minor differences. For example, if the LC says “Fresh Tomatoes” and the invoice says “Tomatoes,” it may still be flagged. When discrepancies occur, the bank issues a discrepancy report, and payment is delayed until the importer approves the documents. Exporters may also face discrepancy fees (USD 100–150 per set). To avoid this, exporters must double-check every document against the LC wording and present them early, leaving time for corrections.

Q25. How many original documents must be presented?

The number of originals required is always specified in the LC. For example, the LC may demand “3 originals and 2 copies” of invoices or “1 original and 3 copies” of the packing list. Transport documents (like truck waybills) often require at least one signed original. Submitting fewer originals than required is treated as a discrepancy. Exporters must carefully read the LC and prepare the correct number of originals and duplicates. Best practice is to prepare one complete master set for the bank and a backup set in case originals are lost in transit. Presenting extra copies also reduces processing delays.

Q26. What if the invoice is not signed?

Unsigned invoices are considered invalid under LC rules. Banks expect the commercial invoice to be signed and stamped by the exporter, as this confirms its authenticity. If an unsigned invoice is submitted, the bank will raise a discrepancy, delaying payment. Exporters should build signing and stamping into their documentation workflow so nothing is missed. Invoices must also carry the LC number, HS Code, quantity, unit price, and total value exactly as required. A properly signed invoice is not just a financial record, it is the cornerstone of LC compliance, linking the exporter to the goods shipped.

Q27. Can documents be presented before shipment?

No. Documents under an LC can only be prepared and presented after shipment, since they must reflect shipment details like dispatch date, truck number, and actual quantities. Presenting them before shipment makes them invalid because they do not prove performance. For example, a waybill must be issued after the truck leaves the warehouse, not before. The bank relies on these documents as proof of shipment, so premature presentation is non-compliant. Exporters should prepare drafts in advance but finalize and present them only after goods are dispatched and supporting certificates (like COO and PSC) are issued.

Q28. Can banks extend LC expiry automatically?

No. Banks cannot unilaterally extend LC expiry. An LC is a legal contract, and its expiry date is binding. If shipment or document presentation is delayed, the importer must request an amendment from the issuing bank, and the exporter must agree to it. Extensions must be made before expiry; once expired, the LC is no longer valid, and banks have no obligation to pay. Exporters should monitor expiry dates closely and request extensions in advance if needed. Depending on the buyer-bank relationship, extensions may also involve extra charges. Relying on automatic extensions is risky, they do not exist in LC practice.

Q29. Why are perishable exports like vegetables riskier under LC?

Perishable goods like tomatoes and onions carry extra risks under LC because even short delays can reduce freshness and market value. If documents are delayed or discrepancies arise, payment may be held back, leaving exporters without funds while goods are already consumed or sold at the destination. Unlike durable goods, perishables cannot be re-exported or stored for long. This makes timely, error-free documentation critical for exporters of fresh produce. Best practices include presenting documents within 5–7 days of shipment, booking inspections early, and keeping backup sets ready. For perishable trade, LC compliance is not just about payment security, it’s about ensuring the business remains profitable despite tight timelines.

Start your Export Import business and take them to international level today with expert support.

Chat with us directly on WhatsApp – [Click Here]

Discover more about us online – [Visit Now]

Learn More with BOAI – [CLICK HERE]

Tags: Ultimate Guide to Letter of Credit (LC) in International Trade and Exports